On November 21, 2011, The New York Times had an article entitled “For Some, Psychiatric Trouble May Start in Thyroid." As a mental health therapist who is hypothyroid, my wife has a particular interest in this subject and pointed out the article for me.

The premise, put forth by Dr. Russell Joffe, a New York psychiatrist, and a group of his professional peers, is that subclinical hypothyroidism may play a significant role in depression. A Brown University professor of psychiatry and human behavior also commented on this connection asking, “Is there an underlying thyroid problem that causes psychiatric symptoms, or is it the other way around?

From the endocrinology side, Dr. James Hennessey, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medcsl Center in Boston, noted "Psychiatric symptoms can be vague, subtle and high individual."

A study, published five years ago by Chinese researchers, gave six months worth of thyroid hormone replacement therapy (see links below for the NIH's info sheet on this medication, levothryroxine and other info from MedicineNet.com), to patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and found improvements in brain scans, memory and executive functions.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0000684/#

http://www.medicinenet.com/levothyroxine-oral/article.htm

So how is this condition diagnosed? and what does your thyroid do anyway? Most of us are familiar with this two-lobed, twenty to sixty gram,two-inch structure, located in the front of our necks and wrapped around our windpipe. It's a hormone producing gland with two products, thyroxine or T4 and its active hormone, triiodothyronnine or T3. I've always thought of its function as a major regulator of metabolism, but in reality that's only one of its duties: it does control how speedily we use energy, but also has a role in how we make proteins, how we react to other hormones and how our bodies handle calcium.

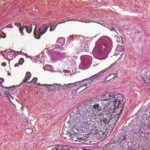

I've spent much of today reading about the thyroid; some things I knew; some I hadn't reviewed since med school basic science classes (1962-1964) and other were brand-new to me. Fetal development of the gland is stimulated by two other hormones released by the hypothalamus and pituitary and those are at high enough levels to cause the fetus to make T4 in clinically significant amounts by 18-20 weeks of gestation. The active hormone, T3, stays at low levels for another 10 gestational weeks, then increases until term.

The net result, it is felt, is protection of fetal development, especially of the brain, in the event the fetus's mother is herself in a hypothyroid state.

But back to adults and the link between thyroid status and mental health. One of the crucial measurements of thyroid function is the level of TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone. Normal levels for this pituitary hormone are 0.4 to 5.0 in most labs in the United States; nearly nine years ago, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommended the doctors consider treating patients whose TSH levels are higher than 3.0. Other scientific groups agreed.

If a TSH level above 5.0 is abnormal, then ~5% of our adult population is hypothyroid. But if that level is reduced to 2.5 to 3.0, then ~20% of us are hypothyroid.

I wonder if a new field of medicine, halfway between the endo folk and the mental health practitioners, is on the horizon.

http://www.umm.edu/endocrin/thygland.htm